Colección de Arte Cantú Y de

Teresa

Mexican Art &

Life (1938-1939)

Mexican Art & Life was an

English-language periodical published by Mexico’s Departamento Autónomo de

Prensa y Publicidad in 1938-1939. Issues cost 15 cents per issue or 50 cents

for a year’s subscription. UTSA Libraries Special Collections holds six of the

seven issues published.

Mexican Art & Life’s topical content is fairly consistent throughout its brief

history. Most issues feature a mix of travel-guide-like promotionals about

tourist destinations, articles on artistic practices or traditions, profiles of

Mexican artists, and commentaries on social or economic issues, as well as

occasional prose or fiction pieces.

The very first issue (Jan. 1938)

opens with an effusive paean to Mexico City, highlighting its Aztec history and

its many North American firsts:

Issue No. 3 (July 1938) follows up

with J. Rodolfo Lozada’s description of a trip to Yucatan, appealing to potential

tourists with lines such as, “The soul of Merida imprisons and bewitches the

wayfarer” and “Awaiting [the traveler] are the ruins of a civilization which,

until a few years ago, only interested the archaeologist but now attract poet

and philosopher alike.” Other featured sites include the Aztec ruins at

Malinalco and the Iturbide Palace (April 1938), as well as Monte Alban and San

Miguel de Allende (Oct. 1938).

Art history topics include Oaxacan

pottery (April 1938), Mexican lithographs (July 1938), Political Caricature in

Mexico (July 1938), 19th century photographic portraits (Oct. 1938), and Aztec

animal figurines (April 1939), among others. Artists profiled over the course

of the magazine include: landscape artist and portraitist Argüelles Bringas and

oil painter Francisco Gutierrez (April 1938); painter Jesus Guerrero Galvan,

wax-and-fabric modeler Luis Hidalgo, and landscapist Dr. Atl (July 1938);

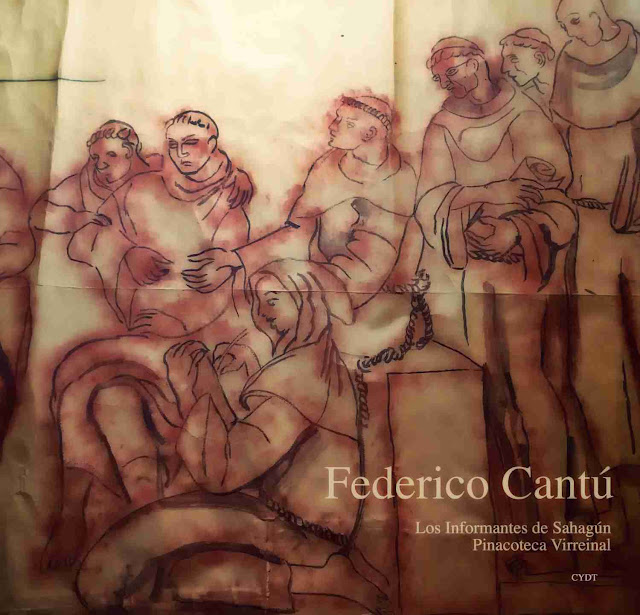

landscapist Jose Maria Velasco and painter Federico Cantú (Oct. 1938); and

photographer Majuel Alvarez Bravo and painter Agustin Lazo (April 1939).

Seeming sometimes at odds with the

celebratory tone and arts & culture of the rest of the magazine are

occasional articles that explicitly address politics and economics. “The Moving

Forces in Mexican Life” (Jan. 1938) draws on a lecture delivered by Dr. Ramon

Beteta, then under-secretary of the Foreign Office” and focuses on the role of

the Mexican Revolution as a social force, its development and future.

“The Indian Problem” (Oct. 1938)

and “Mexico’s Demographic Policy” (April 1939) both make for particularly

uncomfortable reading, although they likely reflected mainstream opinion at the

time.The latter article is especially disturbing when the modern reader looks

at it through the lens of global events of 1939. Author Gilberto Loyo

devotes several paragraphs to discussing immigrants and their relative

desirability based on ethnicity or national origin. In particular, he

discourages Jewish refugees, stating that “The demographic, economic and social

characteristics of the Jews do not make them desirable for Mexico.” On the

other hand, he espouses Spanish immigration (by Spaniards fleeing the Spanish

Civil War) with the explanation that, “a crossing between the Spanish immigrant

and the predominantly indigenous half-breed may take place.”